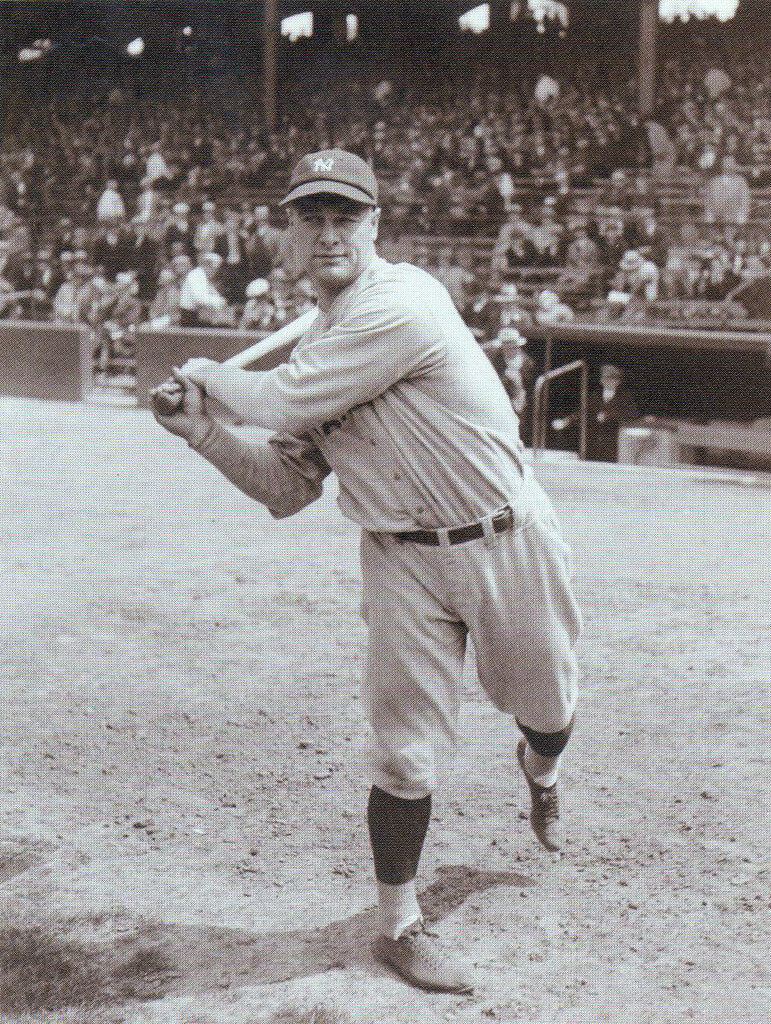

On June 3, 1941, Lou Gehrig died at age 36 of what was thought to be amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. The famous New York Yankee was forced to retire from baseball as a result of the disease two years earlier. His battle with ALS brought attention to this rare and poorly-understood disease, and since his death ALS has come to be known as “Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

But some experts now question whether or not Lou Gehrig actually had the disease that was named after him. There is now evidence of an ALS-like disease associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the neurodegenerative disease thought to be caused by repetitive brain trauma. Gehrig played fullback on the football team at Columbia University, and he had a long history of concussions, including several incidents in which he lost consciousness. Yet, he played through these injuries, setting a record for playing in 2,130 consecutive baseball games.

"Lou Gehrig 001" by rchdj10 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

ALS and Brain Trauma

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease that affects both the neurons, or nerve cells, traveling from the motor parts of the brain to the spinal cord and those traveling from the spinal cord to innervate our muscles for voluntary movements. Both of these neurons in the motor pathway, or motor neurons, are necessary for our muscles to contract and allow us to move. When these neurons are affected in ALS, it causes muscle weakness and eventually paralysis because signals cannot get from the brain to the muscle to initiate movement. Eventually the muscles involved in critical functions such as swallowing and breathing become affected, eventually leading to death. The average survival time after diagnosis is around three years, though a small percentage of patients will live for decades with the disease.

ALS is a rare disease. Globally the prevalence is around 4.4 individuals per 100,000 people in the general population. There are several risk factors for ALS, including older age, male sex, and having a family history of the disease. However, around 90% of cases are sporadic in nature and not linked to a family history.

Another risk factor is a history of brain trauma. The odds of being diagnosed with ALS are around 38% higher in those who have a history of head injury compared to the general population. Those who have sustained multiple head injuries are at a slightly higher odds of developing ALS than those who experienced just one head injury.

Several studies show that the prevalence of ALS is higher in athletes who are exposed to repetitive brain trauma in their sport. Compared to the general population in the United States, mortality from ALS is more than four times higher in NFL football players. Several studies have shown that the odds of dying from ALS are two to ten times higher in professional soccer players in Europe. One study found that the longer a soccer player played professionally, the greater their risk of dying of ALS.

The increased risk of ALS in contact-sport athletes is striking, but also concerning is the age that the disease is diagnosed. In Europe the average age of diagnosis of ALS in the general population is around 65 years old. In one study of European professional soccer players, the average age of ALS diagnosis was 45 years old. Another study found that the diagnosis of ALS before age 49 was substantially higher in professional soccer players. Given the short life expectancy after diagnosis with ALS, having an average onset 20 years earlier than the general population means most of these athletes died years or even decades before the average age most people are diagnosed with the disease. This diagnosis is devastating at any age, but a diagnosis in a person’s 30s or 40s exceptionally tragic.

It’s not known exactly how brain trauma leads to an increased risk of ALS, but there is some evidence that blood-brain barrier disruption might play a role. The blood-brain barrier is a highly selective membrane that regulates the passage of molecules between the blood and the environment around the neurons in order to protect the neurons from potentially harmful substances. Disruption of this barrier that can occur with brain trauma leading to alterations in the environment around neurons could play a role in the development of ALS. Mouse models have also shown that brain trauma can trigger pathology involving a protein called TDP-43, which is found in ALS as well as many cases of CTE.

To be clear, a history of brain injury doesn’t make the risk of getting ALS high. It is still a rare disease even in those with a history of either repetitive or a single brain trauma. The studies of athletes have only been conducted in professional athletes, and the vast majority of athletes never reach that level. At this time it isn’t known whether or not the risk of developing ALS is higher in those who play sports that expose athletes to repetitive brain trauma only through the youth, high school, or even college level.

CTE-Motor Neuron Disease

While the risk of ALS appears to be higher in former professional football and soccer players, there is some question as to whether these athletes actually have ALS or another disease.

In 2010 Dr. Ann McKee and her colleagues at the Boston University Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center published the first study showing a variant of CTE in former athletes that was similar to ALS. In these cases, pathology seen in the brain in CTE also affected the neurons in the spinal cord, leading to symptoms during life that appeared to be caused by ALS. The connection to CTE could only be seen with postmortem examination of the brain and spinal cord tissue.

The prevalence of both CTE and CTE with the motor neuron disease is currently unknown. Without the ability to diagnose the disease during life, it isn’t possible to know how many people have the disease. In postmortem studies of former football players, the motor neuron disease variant of CTE was present in around 6% to 12% of CTE cases. However, individuals or their families are more likely to donate their or their loved one’s brain and spinal cord to research if they think they may have a disease, making this a biased sample. Far more research is needed to determine how common CTE with the motor neuron disease is.

Still, CTE with the motor neuron variant raises questions about the ALS diagnoses in former professional athletes. It is possible that at least some of those athletes may have had CTE motor neuron disease and not ALS. Without examination of their brain and spinal cord after death, there is no way for us to know.

And that bring us back to Lou Gehrig. It is clear that a disease with ALS symptoms took his life, but the underlying pathology that caused his symptoms has been questioned by experts in recent years. Given his long history of brain trauma, it is possible that he may not have had ALS, the disease that is named after him, he may have had CTE with the motor neuron disease. But without the ability to examine his brain and spinal cord, we will never know.